Overview:

For a third of a century after Rome destroyed Carthage in 146 B.C., it faced no seriously threatening enemies in the Mediterranean region. Yet a major challenge was stirring in far-off Jutland. The Germanic Cimbri and Teutoni tribes abandoned their homes in Jutland and began a southward migration in 120-115 B.C. In 113 B.C., they arrived in Noricum, in present-day Austria.

The local tribe in Noricum, an ally of Rome, begged for help against the incursion. The next year, the consul Gnaeus Papirius Carbo marched a Roman army to drive away the intruders. Yet Carbo barely escaped with his life, and his legions were destroyed.

Declining to invade Italy, the Germans then turned west into Gaul, gathering allies such as the Celtic Ambrones. When the interlopers encroached on Rome’s allies in southern Gaul, the Romans in 105 B.C. decided to end the matter and dispatched two consuls, each leading an army.

Totaling 80,000 men and half again as many camp followers, the two armies comprised the largest Roman force assembled since the one Hannibal had annihilated at the Battle of Cannae in 216 B.C. – and this latter Roman force met an equally disastrous end. When the two consuls refused to combine their armies, the Romans were slaughtered at the Battle of Arausio on the Rhone River.

Rome panicked at the terror cimbricus. But inexplicably, the Cimbri marched into Spain on a great plunder raid while the Teutones remained in Gaul. Yet such was the emergency that the Romans overrode their constitution and elected General Gaius Marius, famed for conquering Numidia, to an unprecedented five continuous years as consul beginning in 104 B.C., with the mandate to create a new army.

Heretofore, the right to serve in the Roman army had been based on land ownership. However, the continuous wars against Carthage and Macedonia had kept Rome’s peasant soldiers in the field so long that an increasing number of them had to sell their farms to pay their debts. The slaughter at Arausio further decimated the shrunken manpower pool.

Marius, therefore, completely disregarded the property qualification and instead recruited poor and landless Romans to serve in his army. Fortunately, the Germans’ failure to march immediately on Rome gave him the precious time he needed to train this new force.

In 102 B.C., Marius marched his army of six legions (40,000 men) into southern Gaul to confront the Teutones. By then, the Cimbri had returned to Gaul and the two tribes decided to invade Italy from separate directions – the Teutones along the Mediterranean coast, and the Cimbri through the Alps’ Brenner Pass.

Marius was fortunate to catch the Teutones and the Ambrones after the Cimbri had departed, yet his army still faced great odds since the enemy force numbered 120,000 warriors. He kept his men in their fortified camp, where they repulsed a German attack. The enemy then decided to bypass the camp and march into Italy.

The Germanic horde took six days to march by, and its troops taunted the Romans, shouting, “Do you have any messages for your wives? After all, we’ll soon be with them!” Marius broke camp and followed the enemy to Aquae Sextiae, where he built another fortified camp. Roman slaves drawing water from the river provoked the Ambrones to attack. Marius then launched his soldiers downhill at the Ambrones and crushed them at the river.

Two days later, Marius led his army to confront the Teutones while secretly placing 3,000 Romans in a nearby woods. The Germans filled the plain and charged up the hill at the Romans, who met them with a javelin storm and then drew their swords. As Marius’ men forced back the Teutones, his hidden troops attacked at the enemy’s rear.

The Teutones panicked and retreated to their camp, with the pursuing Romans inflicting great slaughter. The Teutones’ king, Teutobod, and many of the survivors surrendered. The Greek biographer Plutarch reported that over 100,000 were killed or captured, and that in subsequent years the soil, enriched with the rotted flesh of so many, yielded unprecedented bounty.

As the Teutones met their destruction, the Cimbri crossed the Alps. Since Roman consul Quintus Lutatius Catalus had withdrawn his garrisons from the passes, the Cimbri marched through an undefended northern Italy. When they finally confronted Catalus’ men, the Roman troops fled. Meanwhile, Marius returned to Rome and then marched his army to join Catalus’ soldiers. Together, the two armies numbered over 50,000 men in eight legions.

The Cimbri had delayed their offensive believing the Teutones would soon join them. However, Marius told them that they need not worry about their Teutone brothers, saying, “They already have land, and they’ll keep it forever; it was a gift from us.” He then brought out Teutobod in chains. The Cimbri thereupon demanded that Marius set a time and place for battle, and he designated the Raudine Plain at Vercellae near the confluence of the Po and Sesia rivers.

As the Cimbri emerged from their camp, they generated a huge dust cloud that obscured the size of their force – thereby preserving the Romans’ morale, since Marius’ soldiers could not see how greatly they were outnumbered. The Cimbri sent a cavalry force to trap the Romans, but it was defeated by the Roman cavalry under Catulus’ legate, Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Indeed, thanks to Sulla, it was the Cimbri who were eventually trapped and crushed by Roman cavalry.

Marius then ordered that for each Roman javelin, one of the two iron pins affixing the point to the shaft be replaced with a wooden dowel that would break upon impact. When the javelins connected with the opponents’ shields during battle, the weight of the shafts bent the javelins, which then could not be withdrawn and thrown back at the Romans. The heaviness of the embedded javelins eventually forced the Cimbri to throw away their shields.

The best of the Cimbri warriors in the front rank chained themselves together in resolve to conquer or die; the Romans assisted them in the latter. Sulla’s cavalry attack sowed panic, and the enemy survivors fled to their camp with the Romans in pursuit. Enough of the Cimbri survived to yield 60,000 prisoners, but twice as many of their dead littered the field.

Marius returned to Rome for his well-deserved triumph. However, at the time, no one realized that his victory would lead to the destruction of the Roman republic. By recruiting landless men, Marius, and later Sulla and then Julius Caesar, created armies beholden only to them and not to the Roman state. The institutions of the republic could not withstand this irresistible force unleashed upon them. Strong and violent men fought over the body of Rome for the next 60 years, and out of the ashes of the republic emerged the Roman Empire.

This faction rework will be released in winter 2666 by our great-great-great-grandchilds (Kamil2650, Newdresden III and Marsian-Greek Strategos II)

Units

This faction rework adds 20 new units to the Cimbri. Here are some pictures of the new units:

Melee Infantry

Druhtinaz

Loyal to their local chief, these unarmoured warriors rely on speed and cunning. They are adept with spear, axe or sword. They are not highly trained or disciplined but will eagerly smash into enemy lines for glory and loot. If in servitude, they hope that the valour shown may buy them freedman status. They can be excellent ambushers, but are not expected to hold off heavier units.

Hidlisvini

Extremely deadly, very hardy, and capable of launching a powerful charge, these warriors frighten nearby infantry. Axemen like these use a strong shield for defense and a hefty axe for splitting skulls and severing limbs. Howling like banshees, they sprint into battle to butcher any enemy that stands in their way. These warriors are armed in the Celtic manner, and indeed the throwing-axe of the Celts, the cateia, is also called the teutonus.

Akwinaz

These chosen men are relatively poor, but equipped with heavy axes and used to break enemy formations. They are exceptionally tall, strong, and battle-hardened, so are very effective against any unit, even an armoured one. They are also fast and agile, and perfect for flanking manoeuvers, used as the main shock infantry to be followed by other warriors. The literal meaning of their name is “battle boar,” as they are a metaphoric equivalent of the wild boar.

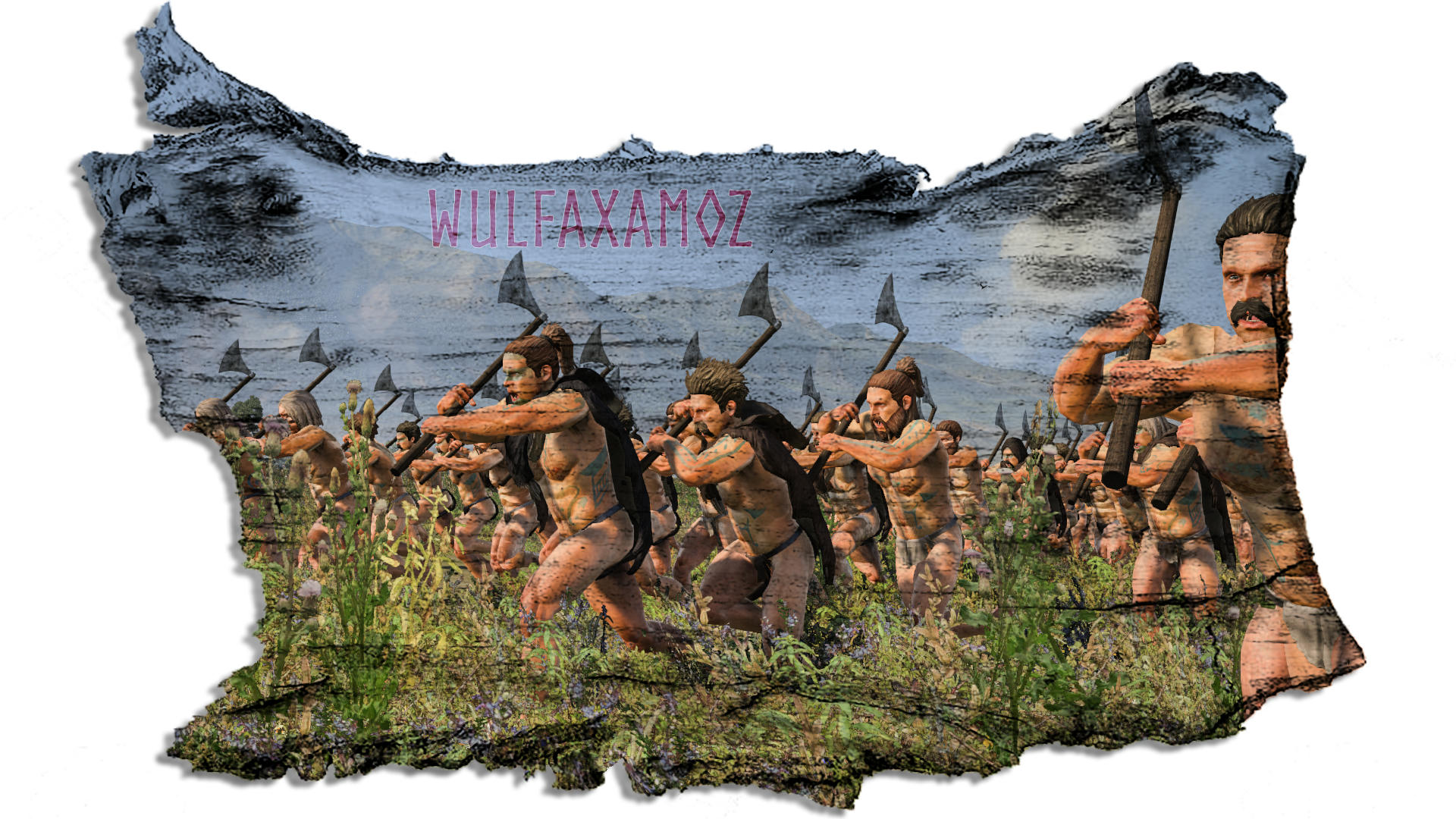

Wulfaxamoz

Finesse is not in the vocabulary of these ‘animals.’ Brute force and viciousness, however, are the norm. All the enemy can see peering out from the tree line is the gigantic shape of a man-bear, with fierce blue eyes burning with a desire to pound them to a pulp. When loosed upon them, this human avalanche of screaming muscle would often break through the enemy line, clawing and battering terror-stricken opponents.

Xerunautoz Xasþaþai

These warriors are some of the more experienced men a Cimbrian leader has to lean on. They launch javelins before engaging hand to hand, but their joy is hacking and chopping with the sword, which can shatter shields, separate limbs and split helmets.

Xaþubarðoz

These well-trained but impetuous warriors terrify nearby infantry with their war cry. Experts at hiding in long grass and darkened forests, they are very hardy and use their single-edged blade with deadly efficiency.

Waiþiz Woþo

Animals, especially wolves, offer much to the warrior bent on going beyond the bounds of his own humanity. He can walk, jump, or run, but also hide, creep, lurk, scream, and howl – wolves often howl in triumph at a kill – and he does all he can to frighten the enemy. The Cimbri have a deep respect for wolves, observing them, copying them, and trying to imitate them. These warriors are stealth fighters, relying on camouflage and trickery to surprise an opponent. Fitted for speed and surprise, attacking and disappearing in hit-and-run raids, the wolf warriors are armed with spear, sword, and shield, and each wears the gaping maw of a wolf atop his head.

Kuningaz Beryanoz

The equipment of these nobles is the finest available; the sword they carry is an extension of their body. They are incredibly ferocious and deadly accurate. They are the leaders of their cantons, and their cantons fight to protect them and earn their favour.

Spear Infantry

Framannoz

The romans call them “framearii” because they are equipped with a framea spear as their main weapon and nothing else. Every man in a village is virtually a warrior, ready to defend his tribe until his last breath.

Ðugunþiz

These warriors are the Cimbrian answer to Triarii. They also pose the greatest threat and defense against enemy cavalry. The framea spear they carry is of the strongest material available, and they are also armed with swords as secondary weapons when bloodlust requires a more personal form of combat. They have more protection in the form of helmets and leather or perhaps bronze breastplates, but fear of death is unknown to these men.

Nakwaðaz

Naked warriors stun and awe enemies not used to their appearance on the battlefield, much like the Suebi Harii who paint themselves and their shields all black to terrorise enemies during attacks at night. These well-trained but impetuous spearmen have no fear of injury or death. Like most Germanic warriors, these hardy troops are experts at hiding in forests and their war cry can cause even veteran warriors to waver.

Thegnoz

These heavy infantrymen carry a stout framea spear, a brightly coloured shield, and a fine sword. The Cimbri are traders of amber, a commodity much sought-after by eastern and Hellenic peoples. The Cimbri obatin quality swords from Dacian or Scythian traders, and these warriors also wear helmets and breastplates made of either bronze or iron. These worthy warriors are capable of holding the line and are also useful as shock troops.

Missile Infantry

Jugunþiz

These skirmishers are primarily younger warriors and hunters. They carry perhaps two or three short-bladed missiles to hurl at the enemy, as well as a combat spear with a longer point to engage in close quarter fighting if needed. Not expected to engage their foes for long like the older warriors, they use their speed and cunning to strike and disappear. Often they are trained by family members and serve their local chief.

Druthiz

This “warband” (Druthi-) is made up of younger warriors, javelinmen for the most part. They learn how to fight with a bunch of light javelins, and carry an affordable wicker shield, as well as a light axe or a dagger like the seaxe as a secondary weapon. Their equipment is cheap, light, and practical, and these warriors are not encumbered by a long spear, so they are agile and useful for quick raids and ambushes.

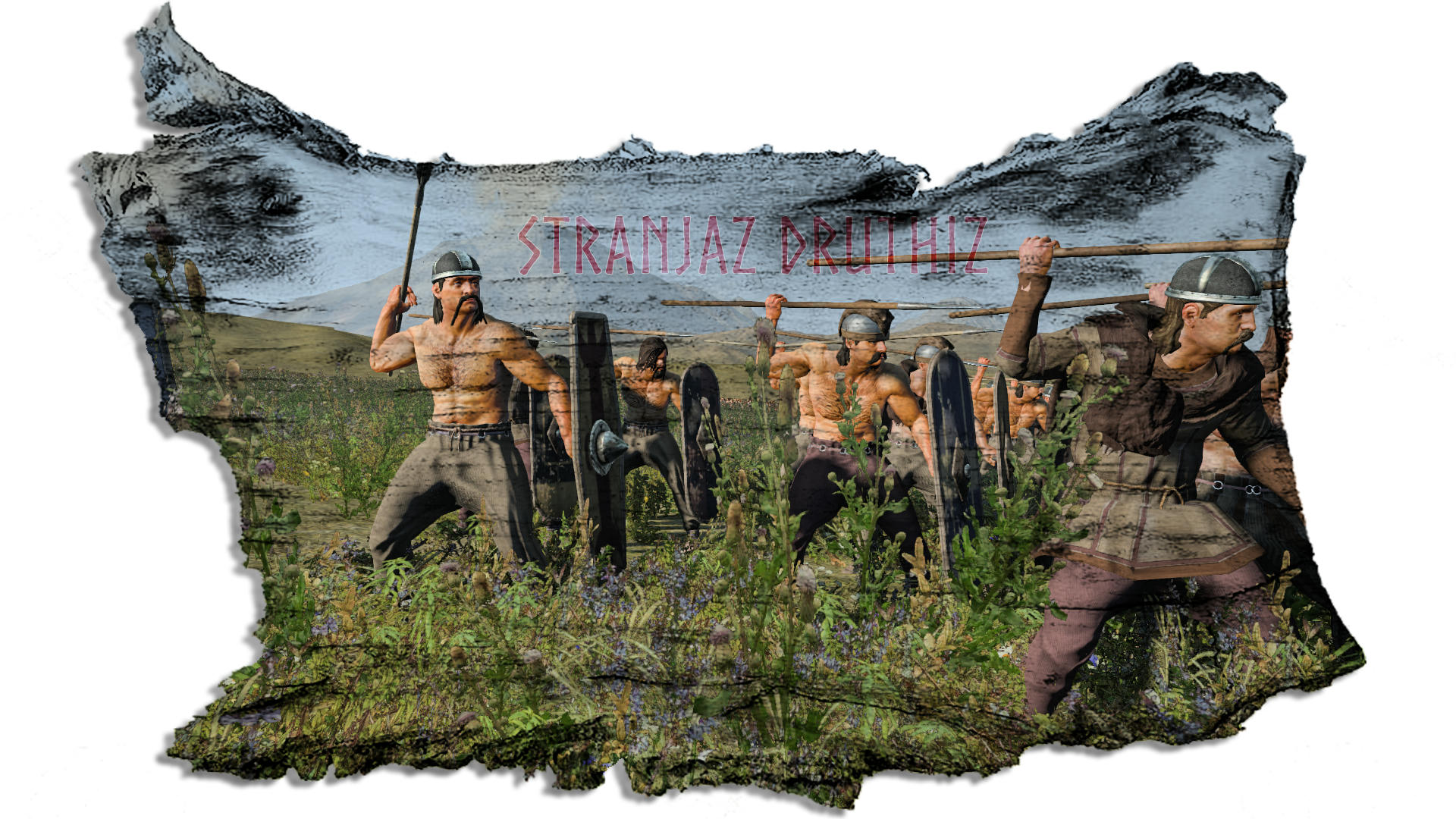

Stranjaz Druthiz

The toughest and most hardened of the skirmisher, these men comprise a canton(100 per unit) from their local tribe, and are better equipped than other skirmishers, most certainly a deadly force on the field. They usually draw first blood in battle after the long and terrifying roar that precedes a furious assault by their brethren. They have stout shields and iron spears, and a few have helmets, most likely a covering made from animal furs to look even more frightening.

Slengwanz

Due to the extensive wandering of this tribe, its slingers have had the advantage of perfecting their art through centuries of contact and alliances with foreign powers. Some slingstones they use have holes through the middle to accommodate the hide sling, so that there is no chance of accidentally dislodging the stone, but the slinger can throw at a velocity that can stun, break bones, or kill.

Skutjanz

Because of their expertise hiding in the forests and fields, or for that matter anywhere, these archers are a deadly threat to enemies. They are used to annoy enemy forces from a distance, or perhaps make cavalry hesitate. They do also carry a spear with them in the event of close encounters, or to support fellow warriors.

Cavalry

Gaisoz Ridanz

Cimbri horsemen are described as not having impressive mounts, but are very well-trained. Often the Cimbri race the tides in their native Jutland, merely for fun and daring. These very hardy horsemen are well-trained at hiding in forests and smart enough to wait for the right moment to strike.

Ridanz

Cimbri horsemen are well-trained enough that even thousands can move as like one, turning to the so perfectly as to not leave one behind or out of place. As heavy cavalry, extremely hardy and well-trained, these horsemen can fight in wedge formation and have a powerful charge. Using the forest to their advantage, they strike terror into nearby infantry.

Marhathegnoz

Cimbri noble cavalry is one of the primary causes for desertion in the enemy ranks. Averaging over six and a half feet tall, they wear helmets representing the heads of wild beasts and other unusual figures, crowned with a winged crest, to make them appear taller. They are covered with iron coats of mail, and carry white glittering shields. Each wields a battleaxe or a large, heavy sword.