Overview:

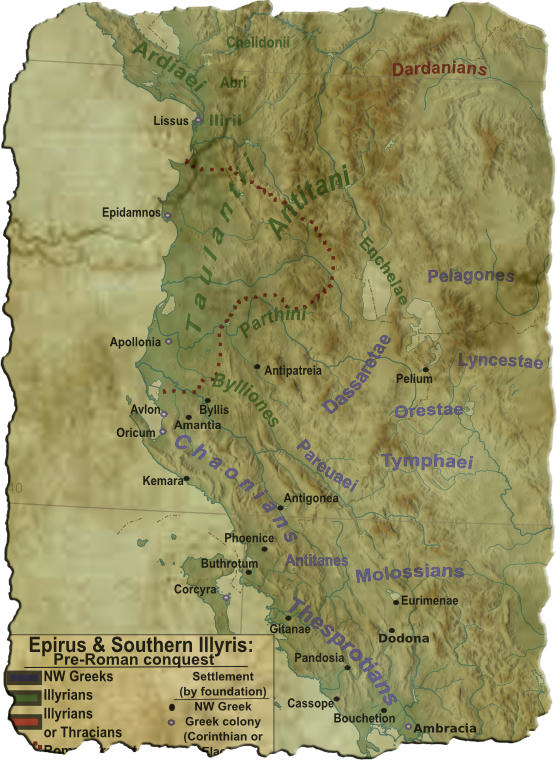

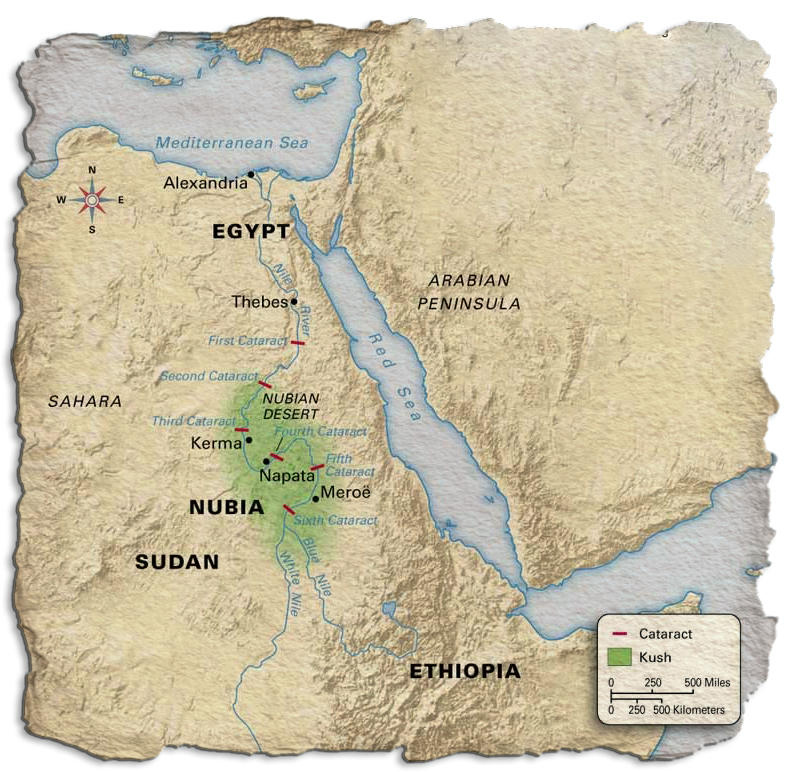

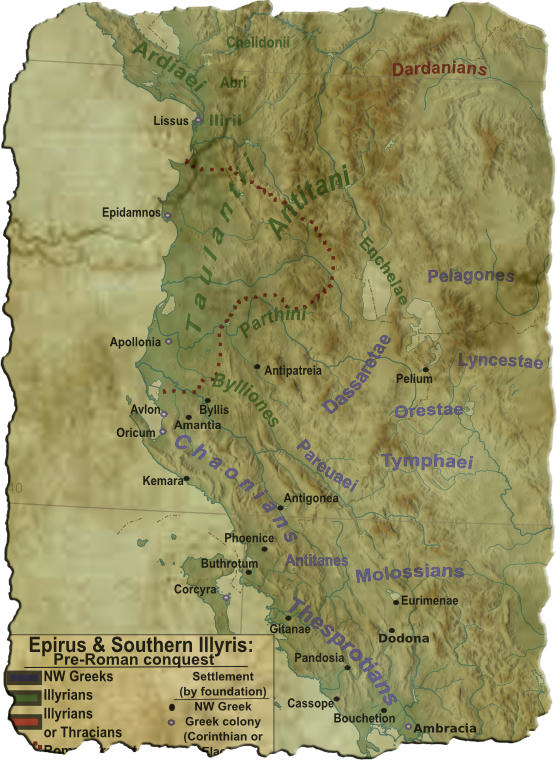

Illyria, northwestern part of the Balkan Peninsula, inhabited from about the 10th century BCE onward by the Illyrians, an Indo-European people. At the height of their power, the Illyrian frontiers extended from the Danube River southward to the Adriatic Sea and from there eastward to the Šar Mountains.

The Illyrians, bearers of the Hallstatt culture, were divided into tribes, each a self-governing community with a council of elders and a chosen leader. A strong tribal chieftain, however, could unite several tribes into a kingdom. The last and best-known Illyrian kingdom had its capital at Scodra (modern Shkodër, Albania). One of its most important rulers was King Agron (second half of the 3rd century BCE), who, in alliance with Demetrius II of Macedonia, defeated the Aetolians (231). Agron, however, died suddenly, and during the minority of his son, his widow, Teuta, acted as regent. Queen Teuta attacked Sicily and the coastal Greek colonies with part of the Illyrian navy. Simultaneously, she antagonized Rome, which finally sent a large fleet to the eastern shores of the Adriatic. Although Teuta submitted in 228, the Illyrian kingdom of the interior was not destroyed, and a second naval expedition was sent against Illyria in 219. Philip V of Macedonia aided his Illyrian neighbours and thus started a protracted war that ended with the conquest of the whole Balkan Peninsula by the Romans. The last Illyrian king, Genthius, surrendered in 168 BCE.

The Roman province of Illyricum stretched from the Drilon River (the Drin, in modern Albania) in the south to Istria (modern Slovenia and Croatia) in the north and to the Savus (Sava) River in the east; its administrative centre was Salonae (near present-day Split) in Dalmatia. With the extension of the Roman Empire along the Danube River valley, Illyricum was divided between the provinces of Dalmatia and Pannonia.

Under the empire, Illyria enjoyed a high degree of prosperity. It was traversed by a Roman road, and Illyria’s ports served as important trade and transit links between Rome and eastern Europe. Copper, asphalt, and silver were mined in parts of the region, and Illyrian wine, oil, cheese, and fish were exported to Italy.

Since the semiautonomous clansmen of the Illyrian highlands were hardy warriors, it was inevitable that the emperors should recruit them to serve with the Roman legions and even the Praetorian Guard. When in the 3rd century BCE the empire began to be threatened by the barbarian peoples of eastern and central Europe, Illyricum became a principal military bulwark of Rome and its culture in the ancient world. Several of the most-outstanding emperors of the late Roman Empire were of Illyrian origin, including Claudius II Gothicus, Aurelian, Diocletian, and Constantine the Great, most of whom were chosen by their own troops on the battlefield and later acclaimed by the Senate.

In 395 CE the empire was finally divided, and Illyria east of the Drinus River (the Drina, in the central Balkans) became part of the Eastern Empire. Between the 3rd and the 5th century it was devastated by the Visigoths and the Huns, who, however, left no lasting mark on Illyria. But the Slavs, who started their incursions into the Balkan Peninsula in the 6th century, had by the end of the 7th century settled throughout the Balkans, including the territories of ancient Illyria.

Ardiaei as an illyrian tribe:

Following the defeat of Carthage in the First Punic War in 241 BC, the Roman Republic became a dominant naval power in the Mediterranean. Nevertheless, Rome’s control of the seas was not absolute. To the east of Italy, another power was on the rise. This was the Ardiaean kingdom, ruled by an Illyrian tribe that began to threaten Rome’s trade routes that ran across the Adriatic Sea. At the helm of this kingdom was the capable Queen Teuta.

Teuta was the wife of Agron, a king of the Ardiaean kingdom. It was under Agron’s leadership that the Ardiaei became a force to be reckoned with. According to the Roman writer, Appian of Alexandria, Agron had expanded his kingdom by capturing a part of Epirus, as well as Corcyra, Epidamnus and Pharus. In addition, Agron’s fleet was much feared in the Adriatic Sea.

In 231 BC, Agron suddenly died, after obtaining a victory over the Aetolians. According to the Greek historian, Polybius, “King Agron, when the flotilla returned and his officers gave him an account of the battle, was so overjoyed at the thought of having beaten the Aetolians, then the proudest of peoples, that he took to carousals and other convivial excesses, from which he fell into a pleurisy that ended fatally in a few days.” As Agron’s heir, Pinnes, was a mere infant when the king died, the Ardiaean kingdom became ruled by Teuta, who acted as queen regent.

Although Teuta continued her late husband’s expansionist policy, her actions have been portrayed in a negative light by Polybius. Though this may well have been a biased view based on his focus on Roman histiography. According to Polybius, Teuta had a “woman’s natural shortness of view”, and that she “could see nothing but the recent success and had no eyes of what was going on elsewhere”. Polybius also mentions that Teuta supported the Illyrian practice of piracy, and pillaged her neighbours indiscriminately, as her commanders were ordered to treat all as enemies.

It was these piratical raids that would eventually lead the Romans to wage war against Teuta. The Roman Senate had initially ignored the complaints made against the Illyrians by merchants sailing the Adraitic Sea. Yet, as the number of complaints increased, the Senate was forced to interfere. The Romans first employed diplomacy, and sent envoys to Teuta’s court. The ancient sources record that Teuta was not at all pleased with the Roman envoys, and was not reasonable in her dealings with them. Worst of all, the diplomatic immunity of these envoys was breached. Polybius records that one of the envoys was assassinated whilst preparing to leave for Rome, whilst Cassius Dio mentions that some envoys were imprisoned whilst others killed.

When news of this returned to Rome, the Romans were outraged, and declared war against Teuta. A fleet of 200 ships was prepared for the invasion, along with a land army. The first target of the Roman fleet was the island of Corcyra, held by Demetrius, who was also the governor of Pharus. In both accounts of Appian and Polybius, Demetrius is said to have betrayed the Illyirians by surrendering Corcyra and Pharus to the Romans. According to Cassius Dio, however, it was Teuta herself who sent Demetrius to hand over Corcyra to the Romans in exchange for a truce. Shortly after the truce, however, Teuta attacked Epidamnus and Apollonnia, causing the Romans to interfere again. Demetrius would later transfer his allegiance to the Romans, as a result of the queen’s capriciousness.

Realising that she was no match for the Romans, Teuta surrendered in 227 B.C. According to Polybius, Teuta “consented to pay any tribute they imposed, to relinquish all Illyria except a few places and what mostly concerned the Greeks, undertook not to sail beyond Lissus with more than two unarmed vessels.” Additionally, Appian mentions that Corcyra, Pharus, Issa, Epidamnus and the Illyrian Atintani became Roman subjects. The remainder of Agron’s kingdom was in the hands of Pinnes, whose new guardian was Demetrius. Although Teuta lived for another few decades, there is an interesting story stating that Teuta had jumped off a cliff instead of surrendering to Rome at Risan, on the Bay of Kotor, present day Montenegro. As Risan is the only town on the bay without a seafaring tradition, it is said that this was due to the curse inflicted by the Illyrian queen on the city before she committed suicide.

Units

This faction rework adds 22 new units to Ardiaei which will replace the existing ones. Here are some pictures of the new units:

Spear Infantry

Illyrioi Pantodapoi

These levies were not well equipped but do their best with their versatile short spear. Sometimes too poor to afford an iron or even bronze tipped spearheads, some of them were equipped with carefully shaped flintstones. When Bardyllis conquered the Scordisci, he succeed to take control of several metallic mines, and enhanced the whole quality of his army… These levies were sometimes equipped with leather soft caps, or in stud, cheap and effective. Their shields were mostly made of wicker or pelt. Wood scutums were probably reserved to the warrior class.

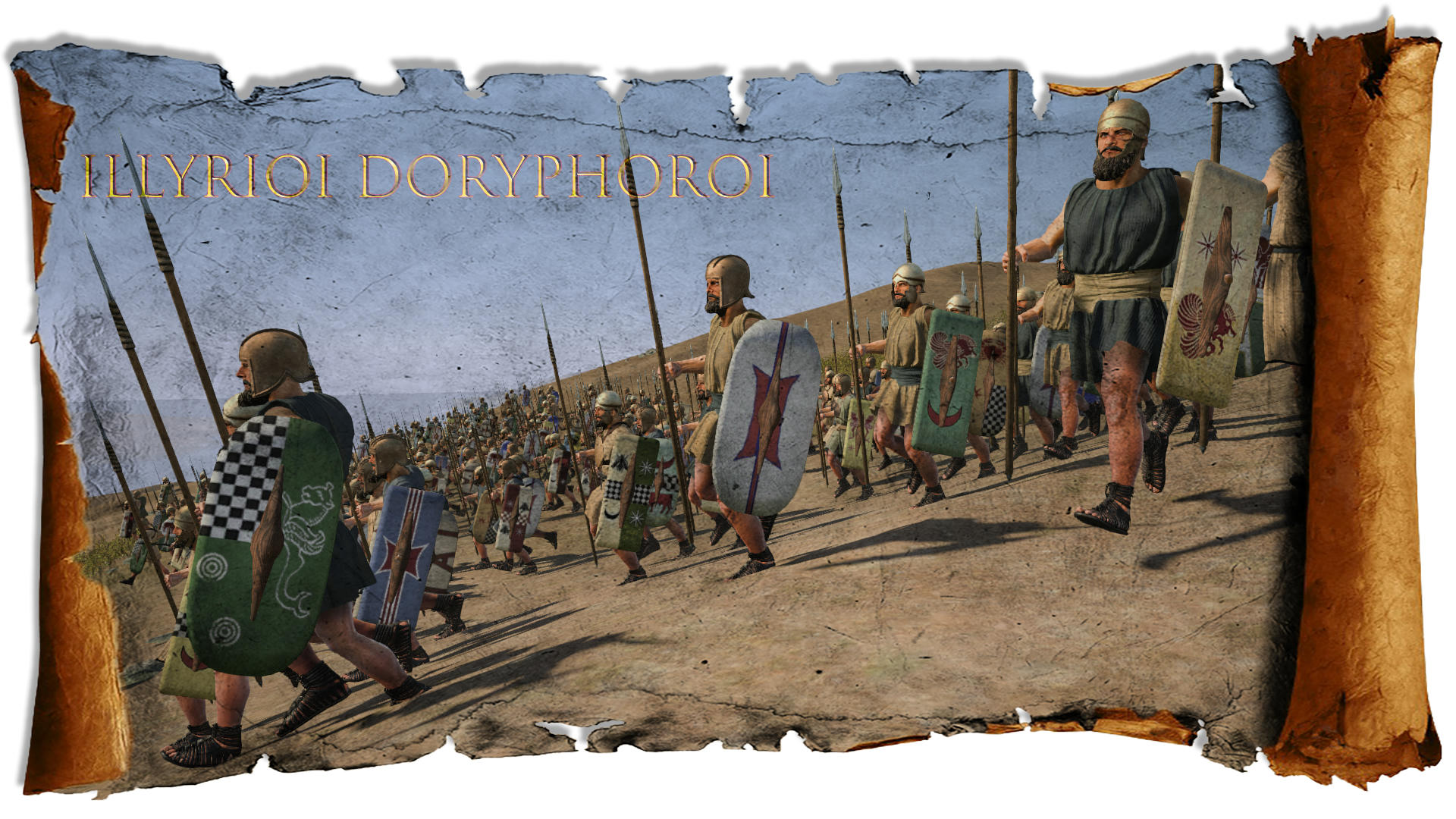

Illyrioi Doryphoroi

The main part of any illyrian army was this kind of levied spear warbands. Raised in tribal aeras, they used various equipments, disc and stud helmets for the most and affordable pot helmets for the others. There main weapon was the spear, sometimes still tipped with a bronze spearhead, although iron was probably more common at that time. Their shield was of various quality, but a scutum, most of the time made with interlapped light wooden boards and leather. Although poorely equipped and almost not trained, they are slightly more experienced and skilled than levied peasants and can hold the line and attack with success if properly managed.

Illyrioi Pantodapoi Hoplitai

Only recruited in major “hellenized” cities (it was always the case for the elites, still under vivid greek influence). The first hoplites were probably introduced by Bardyllis, but it is not clear however if they actually fought like them on only were equipped like them, and still fighting in the classic illyrian behaviour, which made a large place to individual bravery, in the homeric style… Scholars are however more certain about the evolution of these hoplites later. The hoplites of Scodra probably fought while using a real greek phalanx tactic, mostly by imitation to the elite hoplites. Levied hoplites were given no armor, a disc-and-stud or leather cap, and a wide all-wood aspis.

Illyrioi Hoplitai

These standard hoplites could be recruited in southern illyrian major cities, particularly at scodra. Basically they were the so-called “imitation hoplites”, local warriors equipped with hoplite suits, lend by greek allies against macedon. Whatever they could have been effective on the battlefield (they crushed the macedonians, then classically equipped), they were no match against the Lakedemonians… They were given a leather armor, of the illyrian type which was cheaper than the true greek linothorax. They probably didn’t used greaves, or leather ones, as they were reserved to the elite. Well-trained and disciplined, they could slaughtering easily all tribal illyrian troops encountered, and hold fast against similar hoplites, but not against the macedonian phalanxes, as they were crushed by those of Alexander. Later, not suprisingy, they were not efficient also against the Roman legions.

Illyrioi Aristoi Hoplitai (only pre reform)

Only the heavily hellenized nobles of Scodra fought on foot, as their was a strong tradition of horsemanship, and fight dismounted was not a current practice. These “Epiketoi” were given the best equipments, those of archaic hoplites, with the classic bronze armor, greaves, aspis, illyrian helmet (crafted recently, and brightly decorated, not the usual antiquities usually wore by other warriors), xyphos or kopis. Beeing disciplined, they could fight as every elite hoplite unit with perhaps more bravery and temptations of breaking the line to engage more glorious sword duels…

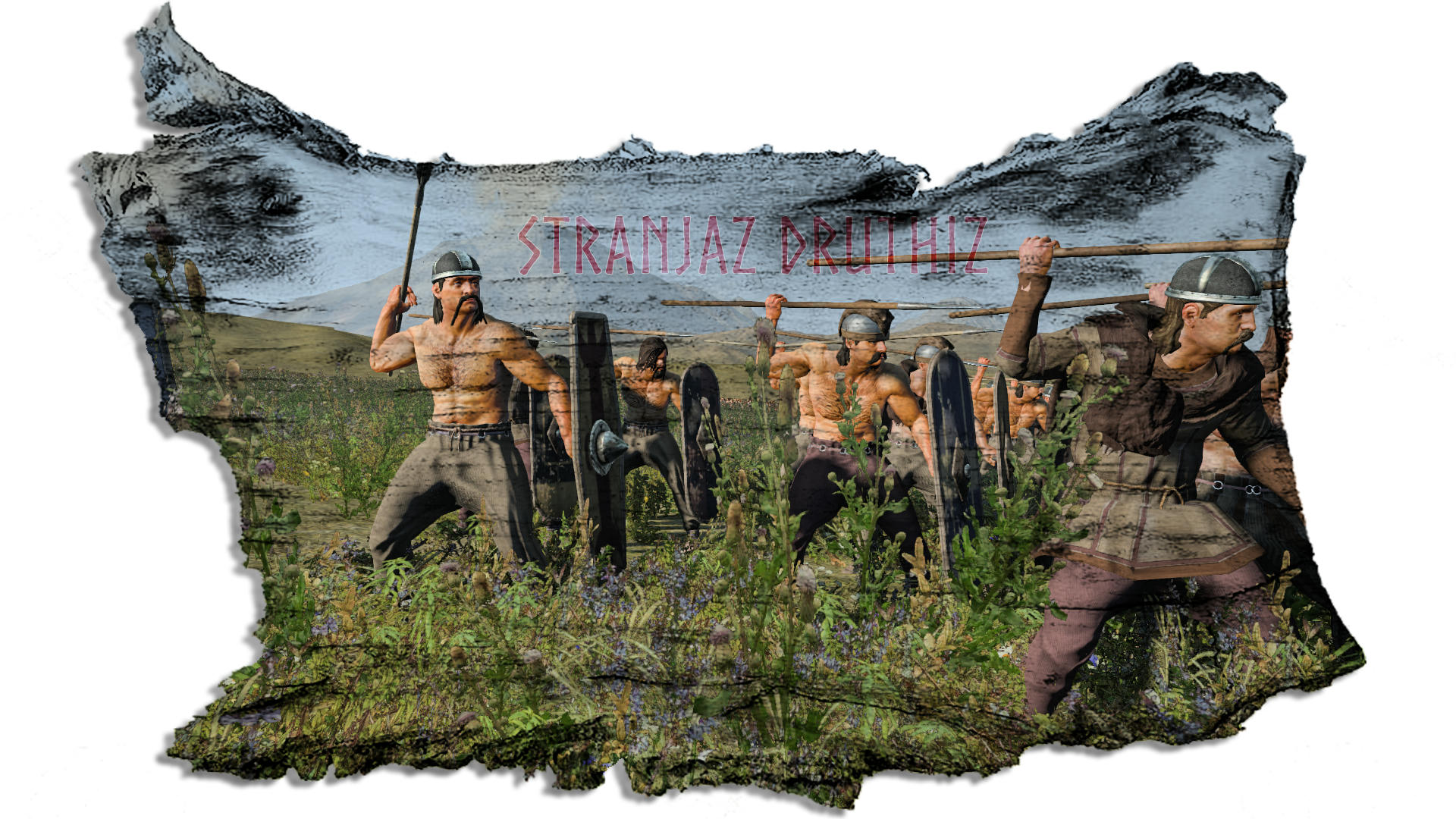

Illyrioi Keles Hoplitai

This kind of hoplite was probably in wide use because of they were equipped with an approximative hoplite wargear, but still retained their illyrian tactics, relying on individual bravery first, and raiding, ambushing warfare. It was however mostly a battle-line infantry, possibly young and weatlhy warriors, were equipped as such. They probably acted as flanking infantry, more mobile in order to counter the enemy’s numerous peltasts like their greek counterparts, but also regularly fought in melee, beeing in huge numbers; The illyrian helmet was either pot or of so-called “illyrian type”. Both were old-fashion and obsolete. It is probably that some of them were given from father to son, and so on, stored and maintained with care.

Illyrioi Epilektoi

These well-trained, well protected and well-experienced scutum bearers were in fact spear and sword armed infantry, fightning at the forefront, with sheer discipline and skills. They were efficient but equipped with a somewhat obsolete equipment, typically illyrian, including their famous curved sword as secondary weapon, and a deadly xyston. They know how to make quickly a celtic-style shieldwall, or even a kind of “turtle”, and slowly advancing against an heavy fire. The celtic and illyrian phalanx made about scutums were even tighter than their greek counterparts… Caesar described them well, and dealt with them by ordering his first line cohorts to hurl their pila on the advancing formation. The pila killed a few, but their shape successfully hampered the entire line by making the shields useless and cumbersome, with these pila deeply encroached. Then, most of these celts throwed away their shield and then were made piecemeal when charging against a second volley of pila from the after ranks.

Illyrioi Eugeneis (reform unit)

This kind of foot noble elite infantry was fighting as hoplites but with a scutum instead the aspis. It was a perfect mix between celtic and greek influences. They used shieldwall tactics with high skills, more in the celtic than greek fashion. If their line was broken, they fought also individually with bravery. As in the celtic battlelines, they fought at the first rank, position of honor. Some of them prefer to used the more prestigious Kopis instead of the classic curved sword. Although bronze and iron armours were obsolete both within the greek and celtic warriors, the illyrians still used and produced them.

Illyrioi Thureophoroi (reform unit)

These late units are partly conjectural. They would have been probably recruited if the roman occured later, and the southern illyrian influence benefiting from returning alexandrian campaign mercenary veterans. This reformated infantry would have been modelled directly after the successors thureophoroi, which probably first seen action by the fall of 300 bc. They were basically improved heavy peltasts, but using a spear as main weapon. The first of them were equipped with greaves but no armour, but the eastern hellenistic late thureophoroi (like the one of Sidon) has more in common with unarmoured roman legionaries than the classic thureophoroi. They could have been related also from players practicing the “thureomachia”, a war-like sport featuring a sword and a thureos. Classic thureophoroi were probably short-lived. According to plutarch, these were peltast, fightning like a light infantry, but then turn quickly to use their spears in phalanx when the enemy was close. They would have been also a variant of the greek mercenary peltastai, and probably the result of iphikratean reforms as well. Illyrians were massively recruited as peltasts, it is near sure that they would serve also as thureophoroi, with hoplite spears, well-protected. These illyrian reformed infantrymen would have worn the usual leather quilted typical illyrian cuirass, and greek more “modern” helmets, like the affordable and widely used chalcidian or attic models.

Melee Infantry

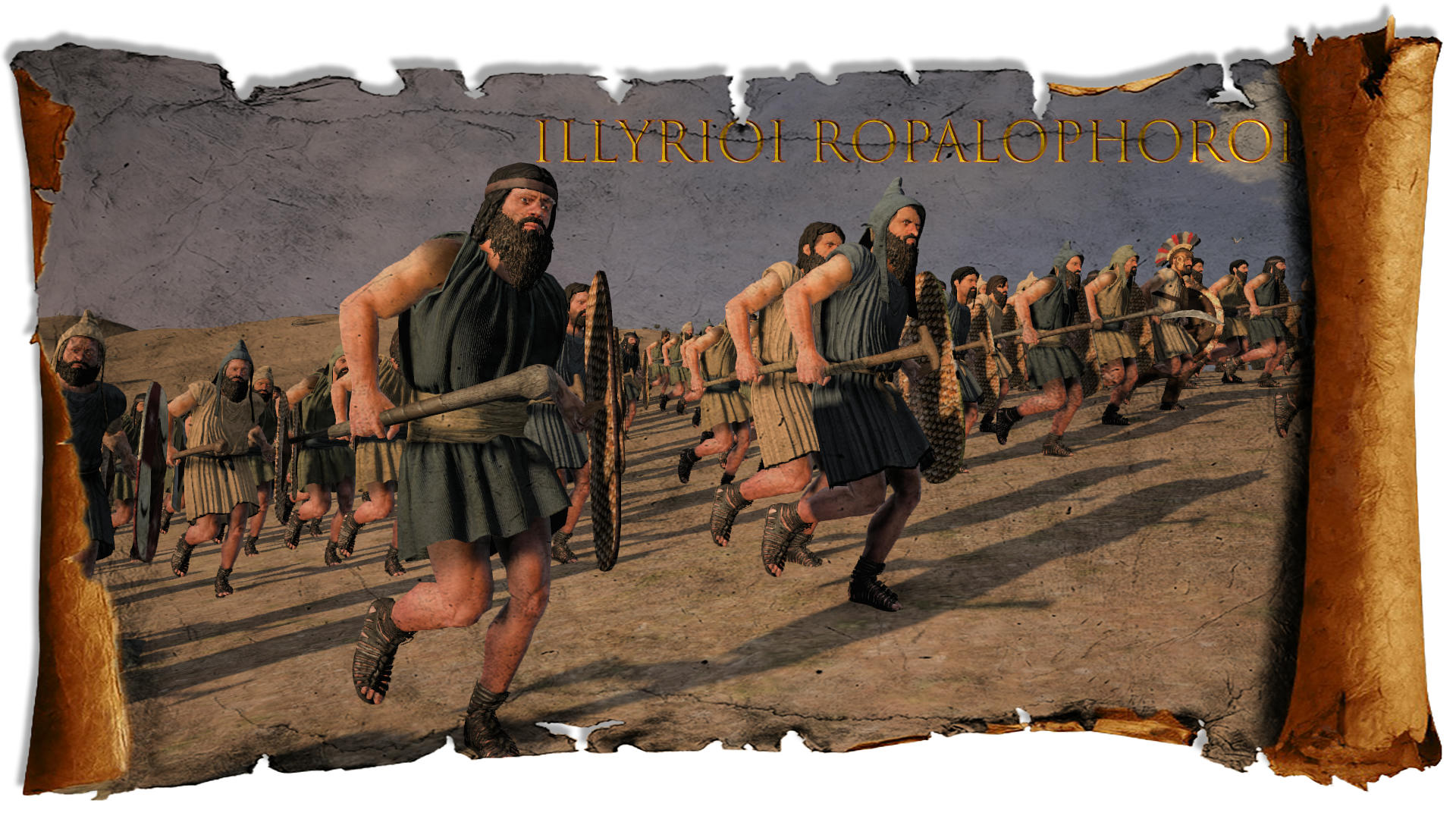

Illyrioi Ropalophoroi

This was the most common infantry within the true warriors. They were poorely equipped, compared to their greek counterparts, but hardened and highly skilled, making them valuable mercenaries for the greek and hellenistic armies. They acted as raiders, beeing equipped with a wood halstatt-style scutum, a mace, stud helmets and a bunch of javelins, not tipped, and a fast-produced wicker and pelt but large and light shield. They mastered ambush and raiding tactics than none in the mediterranean, due to their long intestine wars and mountaneous landscape.

Illyrioi Xypherai

These swordsmen were skilled warriors, fighting with a finely made xyphos, generally similar to the greek models, and also sometimes slightly curved Sica swords. They used bronze helmets, generally of the pot crested type or the “illyrian” model, wood scutum and some iron-tipped javelins. This made them quite efficient as the main assault infantry of any illyrian army. By their equipment they were mostly recruited outside cities. The Bardyllian Scodra warriors were all equipped in a more greek fashion, with aspis and kopis swords instead.

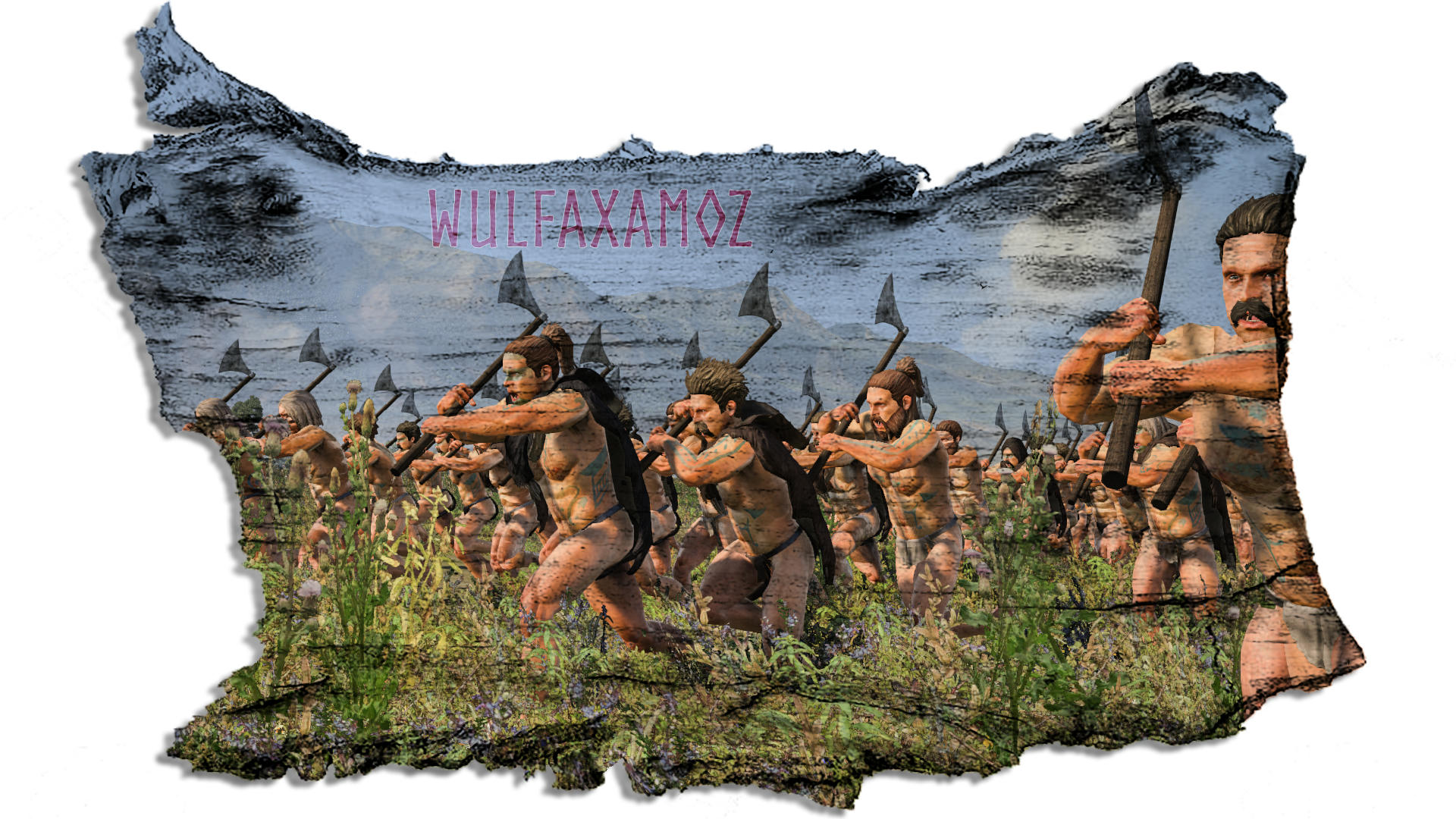

Illyrioi Pelekophoroi

These warriors use a typical illyrian-venetic halstatt axe which was derived from utilitarian “civilian” models with bronze and even flintstone heads. Illyria is a land of mountains and forests, the axe was a very common tool. It is not suprising that the illyrian armies counted lots of axemen, like in nearby Venetic, Boians, Taurisci peoples. This axe is well decribed on some descriptions and reliefs, with a narrow attach, curved handling, and light and long blade. it was more a chopping tool than an heavy axe. But it was light enough to be thrown, these warriors using also javelins as a complement. Their only armor was probably a leather model, which was made of interlapping straps and reinforced by linen and bronze pieces, or a simple leather cuirass reinforced with iron heads.

Dardanioi Epilektoi (reform unit)

Fundamentally, these were elite infantrymen typical of the illyrian kind, but equipped with thracian/macedonian equipments and helmets, like the heavy and modern thracian helmet, hasltatt-style bronze armors, and large and high quality kopis swords. Others used more celticized equipments as long swords and more rarely some chainmails for those who could afford them (like the dardanian nobles). These excellent infantry were lately recruited, in a purely “would if” scenario, as the Dardanians were long time hostile to the southern illyrians, atlhough part of the short-lived “bardylian empire”; They were fierce opponents for both the thracians and the macedonians, and sometimes see as thracians by the illyrians, and the contrary for the first…

Missile Infantry

Illyrioi Akontistai

The main light infantry, common to all tribes included in the Bardyllian kingdom, centered around Scodra. They were given wood javelins, not tipped, and a dagger. Not suited for close combat, they were mostly engaged on forefront skirmishes and traditional ambushes. The Delmatae were the most famous of all, using fur caps and pelt shields. These fierce nomadic people were skilled raiders, accostumed to this kind of warfare.

Illyrioi Toxotai

These commoners were hunters, recruited as auxiliaries, in the typical “psiloi” tradition instaured by Bardyllis. They were not the majority, however, because of the price of arrows. The Illyrians more probably relied upon slingers instead.

Illyrioi Sphendonetai

The slingers were an universal style of warrior, throughout the mediterranean. For some reasons, islanders were generally the best of them. The most reputed slingers were recruited on the Pharos Island, and the Lapodes (north-west) in general were renown. Local reputed mercenary slingers were the Corcyreans. The Liburnian pirates were also skilled slingers.

Illyrioi Peltastai

Really the backbone of any illyrian army, these proven warriors were equipped the curved typical illyrian Sica and an heavy load of javelins. Well protected by their wicker thureos backed with leather, and a leather helmet, they acted as first-class skirmishers or heavy peltasts, capable of close fight as well, with high skills. They were not the majority however, beeing slightly expensive to recruit. Later, they probably became a kind of thureophoroi or elite peltasts, equipped with helmets and operating as a fast wing flanking infantry, replacing the outdated keles hoplitai.

Cavalry

Delmatae Hippakontistai

The Delmatae were the most renown of them. Beeing pastoralists, they used fast horses for scouting an raiding nearby villages. These skilled cavalrymen, if not well-equipped, were efficient scouts and skirmisher cavalry, acting as auxiliaries of the Illyrian army. Light Delmatae infantrymen and cavalrymen wore fur caps, as it was stated by greek authors.

Illyrioi Aspidophoroi

This kind of semi-light cavalry was the most common one. They were given no armor, a leather helmet or metal pot one, and various spears for close combat, for launching and thrusting. They were given also an axe to finish the job. Their main protection was an aspis similar to those of the infantry, although somewhat lighty built. They are well decribed by some engravings.

Illyrioi Hippeis

These lancers were equipped with metal illyrian helmets, leather cuirass, and probably diven from the small local nobility. With their swift and nervous poneys, these well trained cavalrymen were given flanking protection and turning attacks. They can be ordered to threaten the enemy’s back as fightning another cavalry unit, which they do at best, with a medium thrusting spear and their straight or illyrian sword.

Illyrioi Epilektoi Hippeis (only pre reform)

These early bodyguards are a bunch of aristocratic horsemen, heavily trained for mounted combat. They used almost exclusively bronze or iron cuirasses, in the halstatt style, aspis shield backed with wood and covered with embossed bronze. There were not heavy lancers but a fast melee cavary, able to throw javelins and throw a devastating charge with their spears, and finish off infantry with their greek sword, probably machaira, which was highly valued by hellenized southern Illyrians.

Illyrioi Basilikon Hippeis (reform unit)

Late illyrian bodyguards. Although still aristocrats, they would have began to use more refined equipments, and anamorphic cuirass in the thessalian style or chainmails, with the growing celtic influence. They were equipped with spears and spatha longswords, more useful against infantry, and probably adopted from the late celtic heavy cavalrymen. like their fellow celtic noblemen, they mounted huge battlehorses driven from the eastern mediterranean at high price. This mount was necessary to cope with their heavy equipment, roughly the same as an heavy hoplite, and to “push” after the charge, through the enemy lines, striking with their longsword.

Credits:

–assurbanippal for creating the new shields (textures by Ritter-Floh)

– Preview, units, research and overhaul done by Ritter-Floh!