Overview:

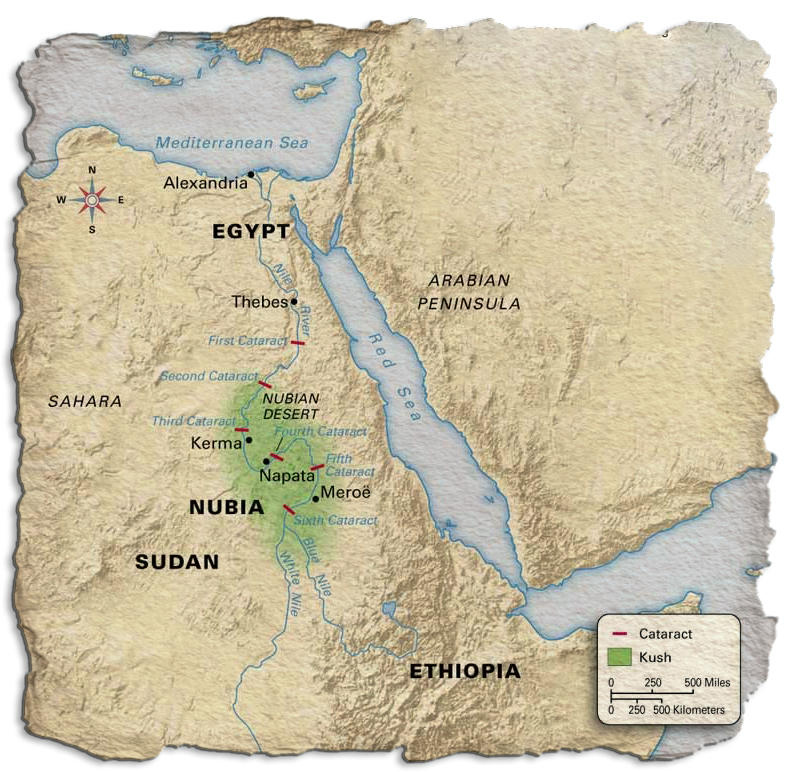

Around 1050 BC, Egypt’s dominion over Nubia came to an end. It was not until approximately 900 BC that a new power subjugated this territory and for no less than 1000 years determined its history. This power, called the Kingdom of Napata and Meroe is also known as the Kingdom of Kush. The Kingdom of Kush is divided into 2 periods, the Napatan Period lasting until 270 BC and the Meroitic Period existing from the fall of that kingdom toward the year 320 AD.

Today we can say, with some certainty that the ruling class in the Kingdom of Kush was not made up of Egyptian or Libyian immigrants, as we had frequently assumed in the past. Names of the royal family as well as high ranking officials and priests, prove that they belonged to the people whose language became the written language of the Meroitic Period. We call them “Meroites”. In addition, the custom of matrilinear succession and the development of royal tomb installations reveal that the social and cultural traditions of the ruling class were derived not from the Egyptians but from the peoples of the Upper Nile Valley.

With regards to agriculture, during the Meroitic Period, cattle breeding becomes increasingly important, replacing sheep and goats due to their nutritional value. The many representations of cattle, for example those in the Temple of Apedemak at Musawwarat es-Sufra, picture a powerful and well-cared-for breed leading us to assume that cattle breeding was taking place. An extensive system of reservoirs was developed to facilitate cattle herding and the cultivation of fields away from the Nile. The vicinity of Meroe was suited to iron production on a large scale. Implements made of iron may have been employed in agriculture and iron tools were used in the quarries and in construction.

The minor arts, especially that of goldsmiths, continued to develop and reached high levels of achievement. The elephant had great significance in Meroe, particularly in Musawwarat es-Sufra where it was frequently represented in relief and sculpture. A significant change took place at the beginning of the Meroitic Period: typical Napatan (bright red) ceramics disappeared entirely. A new black polished ware is found in royal burials beginning around 300 BC.

International trade did not pass through Meroe, which lay to the side of 2 main trade routes connecting Egypt with the Far East [the overland route through Arabia and the overseas passage across the Red Sea]. Direct trade with Meroe was important for Egypt and so was the trade with central Africa states that passed through Meroe en route to Egypt. To Egypt, Meroe exported gold, ivory, iron, ostrich feathers and other products of the African interior; it also provided Egypt with slaves.

The major period for construction of the Musawwarat es-Sufra began after 300 BC with the erection of temples on artificial terraces within the Great Enclosure. This site is located in a natural basin five or six miles in width surrounded by hills in the Sudan. Musawwarat es-Sufra was an important center for pilgrims who came to celebrate the periodic festivals held there for the local gods. The numerous elephant representations may possibly suggest that elephants were trained here (for military and ceremonial purposes) and the large enclosures may have been designed to herd them in. There are several one-room temples dedicated to the native gods.

The Meroitic script has a cursive and more rarely used hieroglyphic form. Despite the individual characters being derived from Egyptian demotic script and hieroglyphs, the Meroitic system of writing differs fundamentally from that of the Egyptian. The complicated Egyptian system was reduced to a simple alphabet of 23 symbols. In contrast to Egyptian script and most Semitic systems of writing, Meroitic script includes vowel notations. From the 2nd century BC on, the Meroitic language was almost employed exclusively as the written language as well. Since there are no bilingual inscriptions to provide us with access to Meriotic, we understand very little of the language.

The history of the Meriotic Kingdom of Kush can be divided into the following stages:

- Transitional Stage 310-270 BC

It was assumed that the Kingdom of Kush was at this time divided into a northern (Napatan) territory with its capital at Napata and a southern (Meriotic) territory with its capital at Meroe. There is a greater emphasis on Amun of Napata as a traditional god. In their cartouches, all the rulers of this period add to their own names the epithet “beloved of Amun.” - Early Meroitic Period 270-90 BC

The influence of the priests of Amun came to an end with the transfer of the royal cemetery to Meroe. Arkakemani is the first king to have his pyramid erected near Meroe. The first 3 rulers of the Meroitic Period assumed throne names modeled upon rulers of the Egyptian Dynasty XXVI. During the reign of King Tanyidamani (110-90 BC), the oldest datable text of significant length written in the Meroitic language is found on a stela containing a detailed government report and temple endowments. Henceforth, Meroitic hieroglyphs were increasingly used and soon replaced Egyptian writing altogether. - Middle Meroitic Period 90 BC~0 AD

The 1st century BC can in many ways be regarded as a golden age; the height of Meroitic power. The strong concentration of reigning queens in this period is striking. A small group of pyramids at Gebel Barkal can be dated to the 1st century BC. Increasing Meroitic activity in Lower Nubia is evident and this eventually lead to a military confrontation with the Romans. According to reports by the Greek geographer Strabo, Roman troops had advanced as far south as Napata. However, a peace agreement with Roman (Ptolemaic Egypt) was met and lasted until the end of the 3rd century AD. Only the Emperor Nero in 64 AD planned a campaign to Meroe, but it was never executed. - Late Meroitic Period 0 AD~320 AD

This period began with King Natakami (0-20 AD). He managed to introduce a new smaller size pyramid and a new kind of chapel decoration. Natakami also carried out renovations for old temples and built new ones. Given the sparsity of surviving monuments, we are forced to conclude that the summit of power achieved by King Natakami could not be maintained in the years following his reign. There are very few observable decisive changes within this period and it is generally regarded as marking the decline and fall of the Meroitic Kingdom. Yet, there is no evidence of impoverishment and the economy worked fine.

Causes for the decline of the Meroitic Kingdom are still largely unknown. Among the various factors put forth are: soil erosion due to overgrazing; excessive consumption of wood for iron production; abandonment of trade routes along the Nile. There were also constant battles with nomads on both sides of the Nile Valley. The Kingdom of Meroe ended in the first half of the 4th century AD.

Units

This faction revision adds 3 new units to Meroe and changes the appearance of many existing ones. Here are some pictures of the new and reworked units:

Spear Infantry:

Yam Suph Gora

(Red Sea Hoplites) These hoplites are mostly Hellenic colonists who were drawn to the Erythraian Sea coast. Their aspis has no bronze coating, relying on elephant skin instead.

Dill’e Gora

(Ethiopian Spearmen) These men are equipped with spears, shields, and helmets the quality of which might change depending who is levying these troops.

Safe Kugur

(Meroe Royal Guard) These elite troops are equipped like hoplites, with a dory spear and a xiphos, kopis or machaira sword. They are useful for many tasks, but are generally foot guards both in camp and in battle, protecting the advance of the king in battle.

Gora’ba

(Meroe Spearmen) Armed with javelins, spear and shield, these troops can skirmish and face enemy infantry in melee. They already know that they are superb hunters and warriors, and do not need to prove their skills to anyone by attacking impetuously!

Nakhtu-aa

(Meroe Pikemen) Based on a Graffiti at Musawwarat es Sufra, these spearmen carry a long spear, swords or maces as melee weapons. As defence they used light armour or just tunics and a smaller shield. They are able to form a phalanx against cavalry and are capable of holding a line against stronger infantry as well.

Melee Infantry:

Qadosh’ba

(Ethiopian Axemen) These fierce soldiers fight with the heaviest of the infantry. They wield large double-bladed axes and fight as powerful shock infantry. They wear a mail vest and leather greaves in addition to a long tunic. Fighting without helmets or shields, these men crash into an enemy line ferociously, using their large stature and raw power to push through enemies with reckless abandon.

Bilit’ti Sayif

(Ethiopian Swordmen) These swordsmen are equipped only with helmets and shields, as body armor would just burden a soldier in the hot climate. They are elite troops, and can be expected to fulfil their role as assault infantry as long as they are properly used.

Dill’e Sayif

(Ethiopian Medium Infantry) Recruited from the lesser nobility of Ethiopian people and equipped with a shield, these troops are very dangerous if used properly. They are the heavy infantry of Meroe generals, and with their axes they can break through an enemy line.

Sipesiye

(Shielded Axemen) Raised from among the higher social groups of the Ethiopians, these noblemen are armed with a double headed axe and a shield. Highly skilled, these men can easily break through an enemy line of lower quality infantry. They can inflict substantial damage, even to well-protected enemies.

Kulus Bomani

(Kushite Painted Warriors) The tribal warriors from the Kushite kingdom are described by Herodotus as half-painted in vermillion and white. They are fierce and versatile, used mostly as heavy skirmishers, fighting with clubs, axes and short spears.

Toog Kugur

(Meroe Macemen) This melee infantry can stike really hard whith their maces, though they are not heavily protected. As weapons they carried javelins and a mace of metal or stone, based on sources from the royal tombs of El Hobagi. A light hide shield is the only defense.

Nass-i Sne (reform unit)

(Meroe Medium Swordsmen) These late Meroe warriors wear the rather strange looking Shotel sword. Recruited from the lesser nobility of Meroe people and equipped with a little shield, these troops are very dangerous if used properly. They are the heavy infantry of Medewi Generals and with their large, curved swords they can break through an enemy line.

Missile Infantry:

Nass’i Wir

(Meroe Archers) These men are equipped with the longbow, similar to some seen in ancient Egypt, as well as a quiver and knife. Their costume also seems to follow ancient Egyptian tradition. Their bows have a short range, but each warrior carries a good selection of hunting and war arrows, designed to cause massive bleeding and pierce armour respectively.

Haug’ba

(Ethiopian Skirmishers) Nubian tribesmen are born warriors; fighting is almost a lifestyle for them. They use mostly short spears, both for thrusting and throwing. They are also accustomed to the harsh conditions of the desert, and are skilled adversaries.

Sipesiye Nass’i Wir

(Ethiopian Noble Archers) Richly attired with expensive pelts and armbands, these nobles have perfected the art of the hunt. Their skill at archery has grown into a specialized art form.

Cavalry:

Haug Mre’ke

(Ethiopian Light Cavalry) These javelin-armed mounted skirmishers can strike quickly and be gone in the time it takes a more ponderous enemy to react. They do not wear armour, but carry shields and swords so that they can fight in hand-to-hand combat should the need arise.

Dill’e Mre’ke

(Ethiopian Lancers) These cavalrymen are often recruited from the higher classes of Ethiopian society, the families of the nobles and priests. They are equipped with lances and swords, in addition to helmets and shields. In battle they can be expected to fight bravely.

Safe Mre’ke

(Meroe Royal Cavalry) These spear-armed cavalry are an elite reserve for use in a moment of crisis. They are equipped with spears, swords, scale armour and shields, so that they can dash to any point on the battlefield and fight.

Sipesiye Mre’ke (reform unit)

(Ethiopian Quilted Cataphracts) Uniquely armored with heavy padding from head to hoof, these fully equipped nobles use maces, swords and spears to inflict heavy damage upon the enemy

Elephants:

Ndovu

(African Elephants) Elephants are a terrifying spectacle to opposing troops, able to smash battle lines and toss men aside like dogs do with rats. They are a living battering ram aimed at the enemy battle line. When pursuing enemies, they can be even more deadly.

Chariots:

Magari

(Meroe Chariots) Light chariots are very fast, very noisy and, when used in large numbers, quite intimidating. They combine the swiftness of cavalry with the ‘staying power’ of infantry. They can also be very effective in pursuing fleeing foes.

Credits: Preview and roster by Ritter-Floh

–assurbanippal for creating the new maces and the pikemen shield (textures by Ritter-Floh)

–Dontfearme22 and the AoB Team for a lot of models/textures. Please check the Age of Bronze mod, it’s an amazing project and the units are very well done!

–The Meroitic Language and Writing System by Claude Rilly and Alex de Voogt for some new unit names (all unit names were held in proto-nubian)

–The Wise Coffin for creating the native language unit names

–LinusLinothorax for his research and help

-The AE team for inspiration and ideas